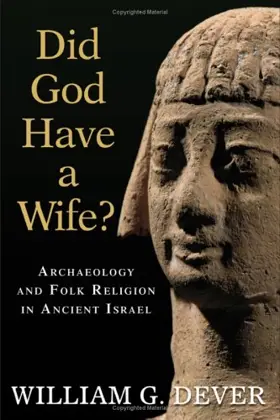

Did God Have A Wife? Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel

The first book by an archaeologist on ancient Israelite religion, this fascinating study critically reviews virtually all of the archaeological literature of the past generation, and it brings fresh evidence to the table as well. While Dever digs deep into the past — revealing insights are found, for example, in the form of local and family shrines where sacrifices and other rituals were performed — his discussion is extensively illustrated and communicated in non-technical language accessible to everyone.

Dever calls his book "a feminist manifesto — by a man," and his work gives a new prominence to women as the custodians of Israel's folk religion. Though the monotheistic faith and practice recounted in the Bible likely held sway among educated, elite men in Jerusalem, the heart and soul of Israelite religion was polytheistic, concerned with meeting practical needs, and centered in the homes of common, illiterate people.

Even more popularly written than Dever's two previous books, Did God Have a Wife? is sure to spur wide, even passionate, debate in all quarters.